Why would a church ask a departing pastor to sign a non-compete agreement? In December 2018, World magazine, a touchstone periodical for a conservative swath of the evangelical world in the United States, published an exposé on leadership issues at Harvest Bible Chapel—a Chicago-area megachurch and the catalyst for a church planting network that counts some 150 independent congregations. Deep within the article, a pastor who departed from his network congregation reported that his resignation process included a pledge not to participate in a ministry “within a 50-mile radius of Chicago.”

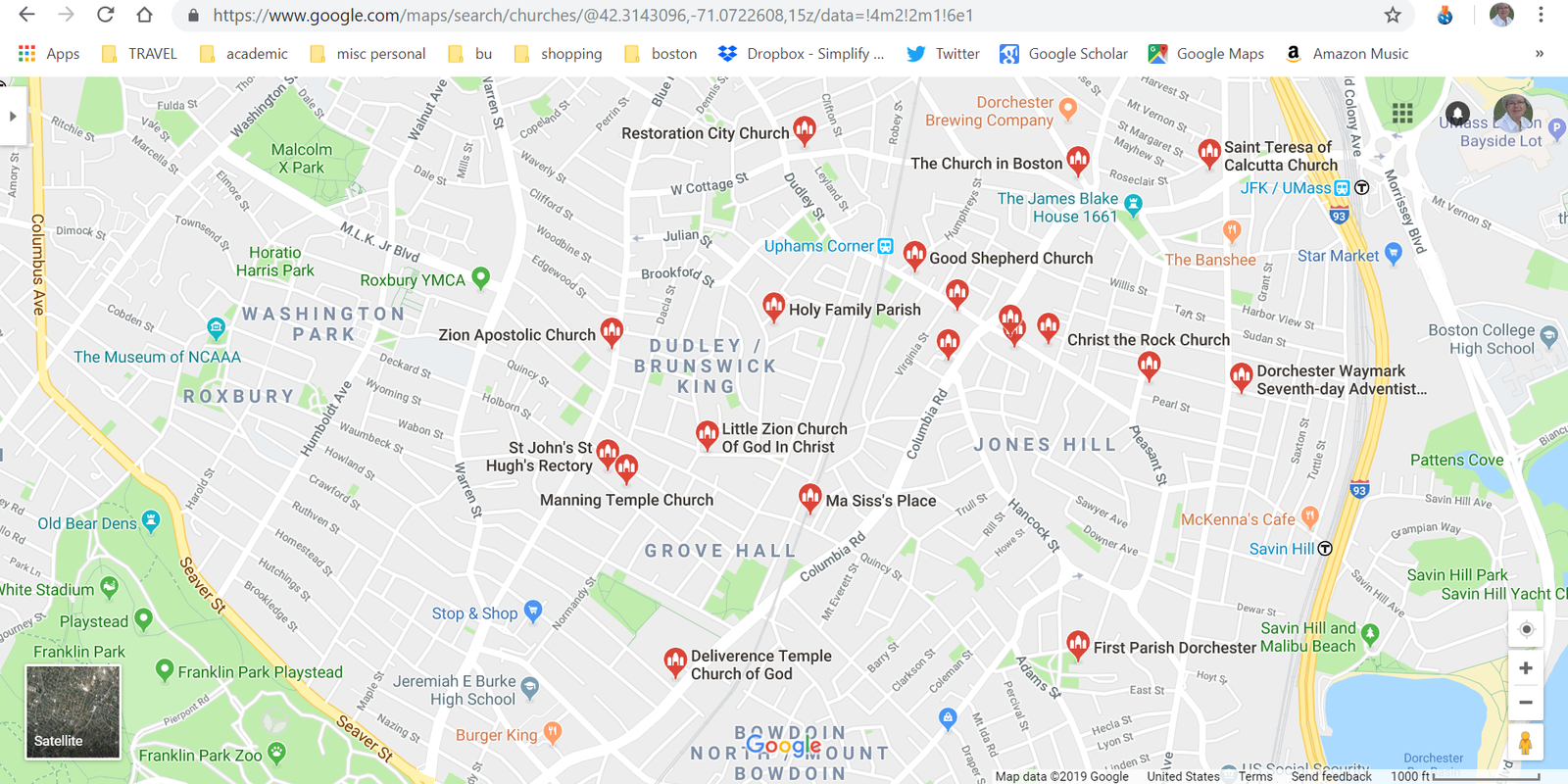

Those geographical restrictions were a clear indication that the Harvest leadership, though they may not have the language, possessed an innate understanding of congregational ecology. That is, congregations act like organisms bent on survival. They seek out nutrient-rich environments and often compete to gain better access to the nutrients — especially people who look like potential members.

Historically, some of the most vivid examples of the dynamics of congregational ecology have occurred as neighborhoods have experienced racial change, and congregations have had to make decisions about how to thrive—or even survive. In Shades of White Flight: Evangelical Congregations and Urban Departure, I wrote about Christian Reformed Church (CRC) congregations that left the Chicago neighborhoods of Englewood and Roseland in the wake of demographic change brought on by the Great Migration, which brought African Americans from the southeast United States to northern cities in pursuit of better economic opportunities, beginning during World War I and continuing into the post-World War II era.

Since churches tend to be bonded by history and ritual – to have a strong internal culture — most congregations find it difficult to adapt to their changing environment. It was no different for these insular CRC congregations. Because they noticed their habitat changing, these largely white ethnic (Dutch) congregations followed their members to ostensibly more hospitable environments in the suburbs.

More recently I’ve been exploring CRC congregations where I now live, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. It turns out that they are somewhat more likely to remain in racially changing neighborhoods. Although this may have to do with their good intentions and commitments, they are also aided by the very different ecological environment.

In Chicago, the vastness of the metropolis meant that newly-suburbanized white families would be hard-pressed to commute 45 to 60 minutes for worship and weekday activities. In Grand Rapids, though, you could be a member of a CRC congregation located in the poorest neighborhood in the city, reside in the sixth-best funded school district in the state, the suburb of East Grand Rapids, and still be only one mile from the church site. In other words, though attenders may have moved, the relatively compact size of the metro-region allowed families to easily commute to the church they have always attended.

To keep them coming and attract new people, however, it became crucial for the congregations to nurture niche identities that would be compelling enough to keep resources flowing back to them in the city. Indeed, my colleague, Kevin Dougherty, and I found that the CRC congregations who had established more specialized identities fared the best. The Madison Square congregation, for instance, seemed to have cornered the market on a CRC version of multi-racial worship and drew commuting attenders from wide distances.

In addition, the ecology of congregations depends on more than raw demographics and potentially competing churches. Other institutions matter, too. In Grand Rapids, for instance, the CRC congregations in the Southeast quadrant of the city proved to be influenced by the decisions and movements of Christian schools, a college from the same religious tradition, and even Dutch-owned businesses.

Congregations, then, don’t exist in a vacuum. You may not be inclined to create a non-compete agreement for your staff, but knowing your local ecology matters a lot. Explore your community with our tools and see what you learn.

About the Author: Mark T. Mulder is Professor of Sociology at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Mulder’s scholarship focuses around urban congregations and changing racial-ethnic demographics. He is the author of Shades of White Flight: Evangelical Congregations and Urban Departure (Rutgers University Press, 2015) and co-author of Latino Protestants in America: Growing and Diverse (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).