Ninety percent of the consumer goods we use daily come to us through the global shipping industry, a sector invisible to most of us and rarely thought about by congregations. Growing attention focuses on the conditions under which goods are made, but what about the people who transport those goods to us?

Every day, across the United States and around the world, container ships and cargo vessels carry food, fuel, and a broad range of consumer goods into ports. In the United States, the Coast Guard and Customs examine the vessel and its cargo. Who cares for the crew? That work falls to port chaplains active at the majority of large ports in the United States and the United Kingdom as well as ports in Europe, Asia and parts of Africa.

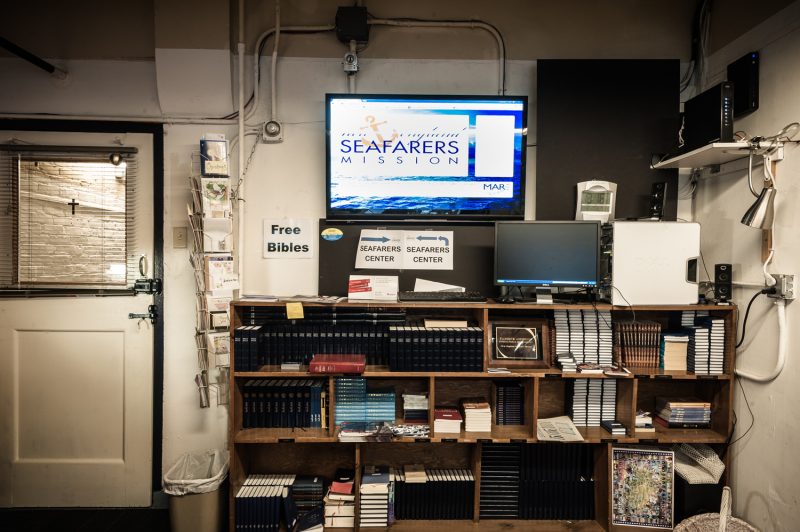

Almost uniformly Christian, port chaplains date to the early 19th century in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Boston, for example, Edward Thompson Taylor and other leaders of Bethel Churches built inns where sailors stayed between voyages. They held educational programs, offered religious services in the sail loft over the arch on Central Wharf and provided religious libraries to departing vessels. Initially focused on both proselytizing and social services, port chaplains today work across religious traditions through the North American Maritime Ministry Association to meet whatever needs – be they spiritual or physical, existential or mundane – seafarers may have.

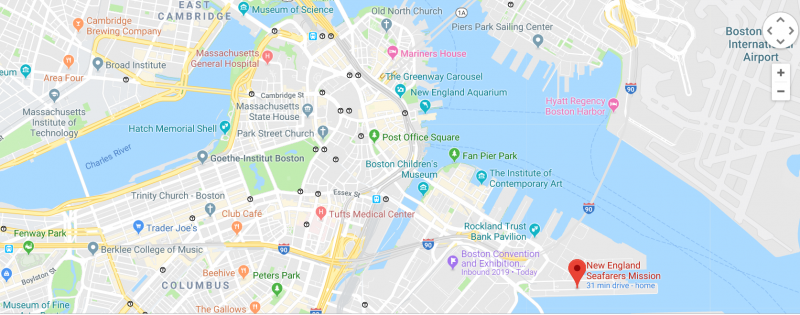

How might local congregations connect with these seagoing populations? Knowing something about the particular nature of your port’s economy helps. In Boston, the work of port chaplains has evolved several times, most recently in 1968 when facilities for container ships opened. Containers allowed crews to be smaller and turnaround times shorter. Rather than bringing seafarers to their inns, port chaplains began to board vessels and connect with crew there. In 1986, when the port of Boston opened to cruise ships, hundreds more workers arrived regularly. As Stephen Cushing, executive director of the New England Seafarers Mission and a senior chaplain himself, told us, port chaplains adapted again – initially offering rows of telephones just off the vessels and helping cruise ship workers send paychecks to their families back in their home countries.

As with the population of any neighborhood, connecting means listening. As we interviewed chaplains in ports across the country, we saw them humanize ports and show foreign workers the United States at its most compassionate and hospitable. They use maps and even cookbooks with photos to act as conversation starters and bridge language barriers. They laugh and joke with crew members who have seen no one but each other for weeks at sea. They talk with seafarers about families, children and the difficulty of being so far away for so long. Chaplains provide support in many moments of crisis, and on occasions that seafarers are not able to continue with the vessel, we have seen how they help with their passage back home.

Some congregations support these efforts today and many more could by reaching out to the port chaplains in their areas. Congregations have collaborated with port chaplains by gathering materials to share with seafarers, knitting hats, supporting Christmas gift efforts, and volunteering. This short video was designed to introduce congregations to port chaplains. To learn more about port chaplains in your area and to find a way to support their work, please contact the North American Maritime Ministry Association. Your neighborhood may be bigger than you think!

Wendy Cadge is Professor of Sociology and Senior Associate Dean for Strategic Initiatives at Brandeis University. She founded the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab in 2018 and is engaged in numerous projects to develop the field of spiritual care across the many settings where it takes place. Michael Skaggs is a Research Affiliate of the Center for the Study of Religion and Society at the University of Notre Dame and the founding Executive Director of the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab. In addition to numerous publications on their own, Cadge and Skaggs have published their work in the International Journal of Maritime History, The Conversation, and elsewhere. Thanks go to the Louisville Institute for funding that supported the creation of the video “Chaplaincy to Seafarers.”