What might we see and hear if we asked worshippers about what they experience? It isn’t always what theologians expect.

For the past few decades, many Catholic liturgical theologians and others have expressed concern about the return of a ritual practice that they worried signaled a regression from the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. That practice is Eucharistic adoration.

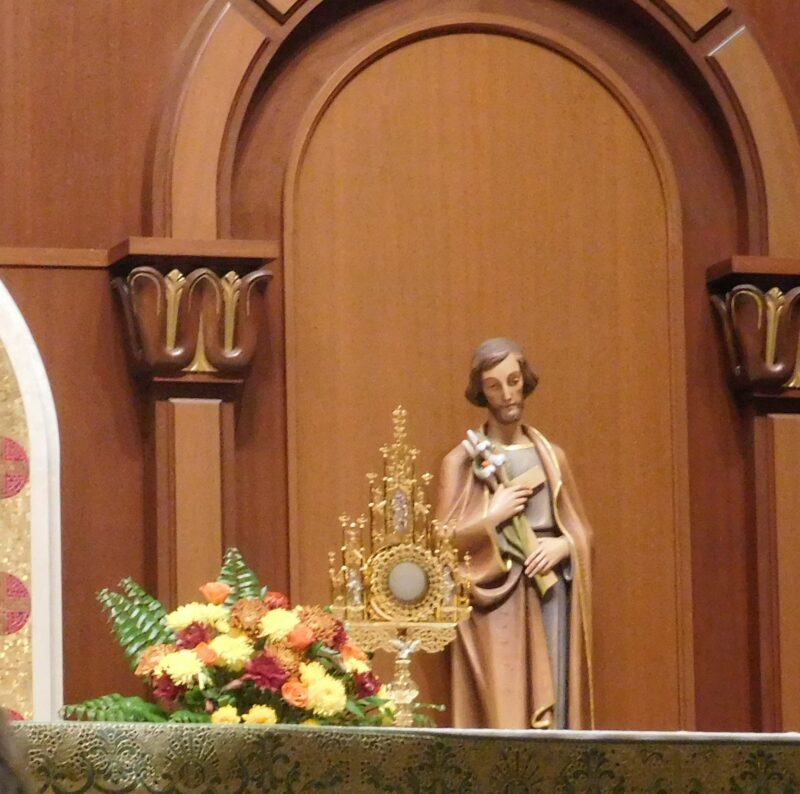

In Eucharistic adoration Catholics prayerfully gaze upon (adore) the Eucharistic host that has been kept in the tabernacle (reserved) following a recent Mass. During adoration, the reserved Eucharist, which worshippers believe is the Real Presence of Christ, is displayed in a vessel called a ‘monstrance,’ which holds and highlights it.

The Mass ends with the missa, which sends worshippers forth to proclaim the gospel by their words and deeds. The reserved Eucharist is then meant to point to the communal worship of the Mass and its missa. Some were concerned that Eucharistic adoration had the opposite effect: it isolated worshippers in silent prayer at the expense Christian action.

As a practical theologian, I appreciated this concern. As a practicing Catholic, I had also personally experienced transformation while participating in this practice. In order to understand what this means for contemporary church life, I set out to study people’s lived experience of Eucharistic adoration.

Studying Worshippers’ Lived Experience

The worshippers I observed represent a range of demographics and adoration settings: a typical weekly Eucharistic adoration that spanned two hours on either side of the end of a typical workday, a perpetual adoration chapel where the devoted are present at all hours of the day, and a university setting that has a history of facilitating Eucharistic adoration accompanied by “praise and worship” music.

I participated alongside these devotees and subsequently interviewed them for around 35 minutes each. I identified themes and used software to show how pervasive and how frequently mentioned these themes were.

“Every single interviewee noted that they felt a sense of healing when they came to Eucharistic adoration.”

Worshippers Leave Adoration Ready to Serve

Every single interviewee noted that they felt a sense of healing when they came to Eucharistic adoration. Carla (a pseudonym, as are all names used here) was in adoration longer than anyone else I observed. She had lost her 33-year-old daughter on the same day one year earlier. She expressed this healing thus: “God knows what you need, what you deserve. He gives you whatever you need. He loves you!”

Eucharistic adorers certainly found comfort in the Eucharist, but to ascertain whether they felt sent forth (missa), I asked informants how they felt when they left adoration. When the conversational dynamics allowed, I asked them if they felt energized. If they answered in the affirmative, as all but one of them did, I asked to what they felt energized.

Ezekiel is a self-described cynic. He leaves adoration feeling a restored sense of optimism and hope. Samuel is short-spoken, but his job is to minister to college students. When he leaves adoration, he feels like talking to people more. Evangeline is a Ph.D. student interning as a clinical psychologist serving minors in difficult situations. Adoration “relaxes me, but simultaneously gives me the energy I need to continue, because I’m rooted in that moment of peace with Jesus.” Mariana, who is “all over the place all the time,” said she does not feel energized leaving adoration. She reports feeling “grounded.”

Carla has summed up this research’s finding: in Eucharistic adoration, worshippers first find healing and then “whatever they need” to go forth and positively transform their community.