The emergence of nondenominational media productions online points to the importance of expanding your sense of what constitutes your congregation’s ecology. It also challenges congregational leaders to think about the culture of their congregation. These are new communities longing for connection, who don’t fit existing patterns of gathering. What might these two innovations tell you? And what might congregations tell these gatherings about how to build and sustain community?

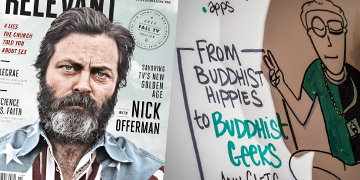

RELEVANT MEDIA

Cameron Strang founded RELEVANT Media Group in 2000 when he was 24 because he could not find a Christian platform that spoke to his peer group, and, as he puts it, “Sunday morning was not fulfilling.”

In one sense it is an innovative move to create a media platform that blurs distinctions between the sacred and the secular. On the other hand, media production has long been a part of American religious life. By 2014, RELEVANT was reaching well over 2 million twenty- and thirty-something Christians a month through a print and iPad magazine, daily web content, videos, live studio recordings, and a weekly podcast.

Strang describes a generational disconnect between “the church we grew up in and the faith we wanted to play out.” He and his readers find God alive and speaking in all aspects of life, even those that are nominally secular. From the beginning, the inclusiveness of the group’s content—ranging from spiritual growth to career, relationships, and popular culture—distanced it from other Christian media and denominational gatherings. They often condemned or excluded RELEVANT, but Cameron views the lack of support as a blessing, in that independence allows the company to remain nimble and innovate. But it has been hard.

While open to the possibility of partnering with a missional Christian organization, Strang wants RELEVANT to continue at a speed boat pace amidst denominations that, like cruise ships, are inevitably slow-moving. Tellingly, many of the young Christians who follow RELEVANT content do not belong to a congregation. This raises questions about if and how this online audience might become a community.

“This raises questions about if and how this online audience might become a community.”

The RELEVANT podcast is a potent example. In 2005, the group began producing a weekly podcast that resembles a late night talk show, featuring bands and guests. The show developed a loyal fan base and got up to half a million downloads per week. For the tenth anniversary, RELEVANT invited an audience to sign up online and come in for a live recording. As Strang describes it, the team was floored that around 800 people came, flying in from all over the country and the world for the 2-hour episode.

Even more striking than the turnout, was the way people described their relationship to the podcast: “You guys are my church, my weekly connection with other Christians who see the world as I do.” “I got hurt in my church and I didn’t walk away from God because of your podcast.” “I started listening in high school and now I’m a doctor. I’ve moved to different cities and different jobs, but this has been a stable part of my life.”

The RELEVANT team had talked about having events for a long time. Given the evident, unmet yearning for community, it took on new urgency.

BUDDHIST GEEKS

Buddhist Geeks is an online community of Buddhist practitioners exploring the intersection of a 2,500 year old lineage together with the reality of rapidly evolving modern technology in a global culture. WIRED magazine describes the big questions the community asks as, “How can social media support meditation practice?” “How can design thinking change the way ancient wisdom is taught and passed on?” and “Can video games lead to enlightenment?”

Vincent Horn and Ryan Oelke founded Buddhist Geeks in 2006 after studying at Naropa University in Boulder, CO and grew the first offer, a podcast, to over 100,000 listeners every month by 2009. The first attempt to build a community around the podcast had mixed results. Hundreds came from across the country and farther afield to the first in-person gathering, and meet-ups kept growing. But, explains Horn, “We went too far in the direction of being self-organized and ended up too decentralized.” That meant that Horn and his team had “built a community we didn’t always want to be part of and couldn’t lead” which led to some concrete difficulties. “Because of the lack of leadership we never got off the ground financially. We were in the land of the living dead! That’s where our mentor and business advisor really made the difference. Without that support and coaching, we wouldn’t have made it through the dip.”

Horn and his team struggled to find others building similar communities so there wasn’t much of a roadmap for how to develop. “I would have loved peers to compare notes with,” he says. “The for-profit sector has various incubators to help you connect with collaborators, grow the organization and decide what kind of investment to take – we would have loved something like that.”

Today, Buddhist Geeks is a vibrant community that, alongside the podcast, offers online meditation spaces, one-to-one teaching, an in-person retreat, an annual conference and at-home Life Retreats, which builds a small group of peers to grow in their practice together. Community members will often post on the Facebook group that they’re going to meditate in the next ten minutes and link to a Google Hangout link, where others will join them simply to sit together – connected across space and time.

With a new leadership team, Emily and Vincent Horn, there has been a stronger focus on engaging female Buddhist geeks (including changing the logo to feature a woman) and there’s a strong focus on Big Tent Buddhism, honoring various lineages, traditions and systems of practice. Horn explains, “Though there’s a clear lineage of training for both of us, we’re very much about remixing and hacking traditions.” With 110 paying community members, Buddhist Geeks has found a financially sustainable model and is training new leaders to become facilitators and teachers.