Most congregations pride themselves on being open and welcoming to newcomers. They might station greeters at the doors. Some offer small gifts in the lobby for those who are visiting. Others might ask for contact information in order to follow up. However, many congregations in the United States are failing to welcome a rather large segment of the population, one that most likely never even makes it through the front door for a worship service.

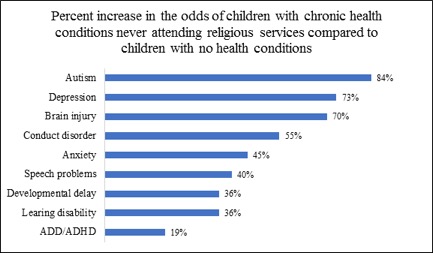

In a recent study I found that children with chronic health conditions are much more likely to never attend religious services than children with no health conditions. In fact, the odds that a child on the autism spectrum never attends religious services are almost double those of a child without a health condition. The odds for children with depression or a developmental delay are 1.7 times and 1.4 times higher, respectively.

I also found that these relationships are stable over time. This means that over the course of a whole decade, children with chronic health conditions were not attending religious services any more (or less) frequently.

Finally, as you might notice from the figure above, the chronic health conditions that are most influential in limiting children’s attendance are those that affect communication and social interaction. Chronic health conditions that are more physical in nature do not appear to limit children’s overall attendance rates in the same way.

Why are they absent?

Researcher Erik Carter finds that individuals with disabilities are no less likely than those without a disability to consider faith to be important. Americans with disabilities and their families want to participate in organized religion. What is keeping these children and their families from attending religious services is the congregations themselves.

In his thorough yet accessible book, Carter outlines five different barriers that faith communities tend to create that limit the inclusion of people with disabilities. They include:

- Architectural – are there ramps for people with wheelchairs?

- Liturgical – are the rituals or sacraments adapted to meet individual needs?

- Communication – are visuals, lights, or sounds adjusted for those with special needs?

- Programmatic – are there additional supports in place so those with disabilities can participate?

- Attitudinal – do leaders or members of the congregation harbor patronizing, disparaging, or paternalistic attitudes toward those with disabilities?

One out of five Americans reports having at least one disability. Are one in five of your congregants or fellow worshippers disabled? If not, it may be because your faith community or congregation presents barriers to inclusion and participation.

As you think about where your congregation may or may not be welcoming, think about your congregational culture, as well as about the resources you can bring to bear. As you do that inventory, our toolkit is here to help. And here is additional reading and resources that can help.

Erik W. Carter, Including people with disabilities in faith communities. Available on Amazon.

Andrew Whitehead, “Religion and Disability: Variation in Religious Service Attendance Rates for Children with Chronic Health Conditions.” Available here and for free here.

Resources from Autism Speaks for “Parents and Families” and “Religious Leaders” available here.

Find “Welcoming People with Developmental Disabilities and Their Families: A Practical Guide for Congregations” here.

And statistics on the number of Americans with disabilities come from the Centers for Disease Control and can be found here.

Andrew Whitehead is an assistant professor of sociology at Clemson University where he primarily studies disability and religion as well as Christian nationalism. You can follow him on Twitter @ndrewwhitehead or peruse his faculty page here.