If ‘congregation’ implies gathering, March 2020 created a seismic shift that has fundamentally altered congregational life. If we are able to return to pre-pandemic habits sometime soon, which of the new habits will remain?

Thinking about that question will require the sort of careful assessment long-time congregation watcher Jack Wertheimer has offered in a recent essay, “How Will Synagogues Survive?”. He comes to his wisdom by asking good questions and gathering good data.

He conducted over 50 interviews with rabbis and denominational officials, reviewed websites, and engaged lay people in informal conversations. It’s not a random sample, but the range of people he interviewed gave him a deep picture of what has happened and a base from which to think about the future.

Most especially, the questions he asked took account of the full range of factors that shape congregational life, something this website is designed to help you do. Follow the links to learn more.

How did (and will) the essential culture of synagogues change? If Jewish gathering is about learning, prayer, singing – and eating – how were those functions present (or not) when people couldn’t gather in person? What new opportunities for learning arose when it was virtual and asynchronous, when people could study from anywhere on their own schedules? Did they sing and pray along when they were by themselves or just with family (and did they miss hearing the other voices)? And are they eager to return to kiddush?

And what have we learned about how we care for each other and the world? Are there new ways of organizing and delivering mutual care that can and should endure? What about engagement with justice and care for the earth? Wertheimer reports that many synagogues continued and expanded this work, in spite of not gathering in person.

Relationships and networks have changed, too. People with disabilities, scattered families, and former members, all have gathered on Zoom in ways that have enriched connection. As Wertheimer points out, even those who are always at the back of the sanctuary have reveled in their ability to see faces and be in the midst of the worship ‘action.’ How will congregations keep these networks alive?

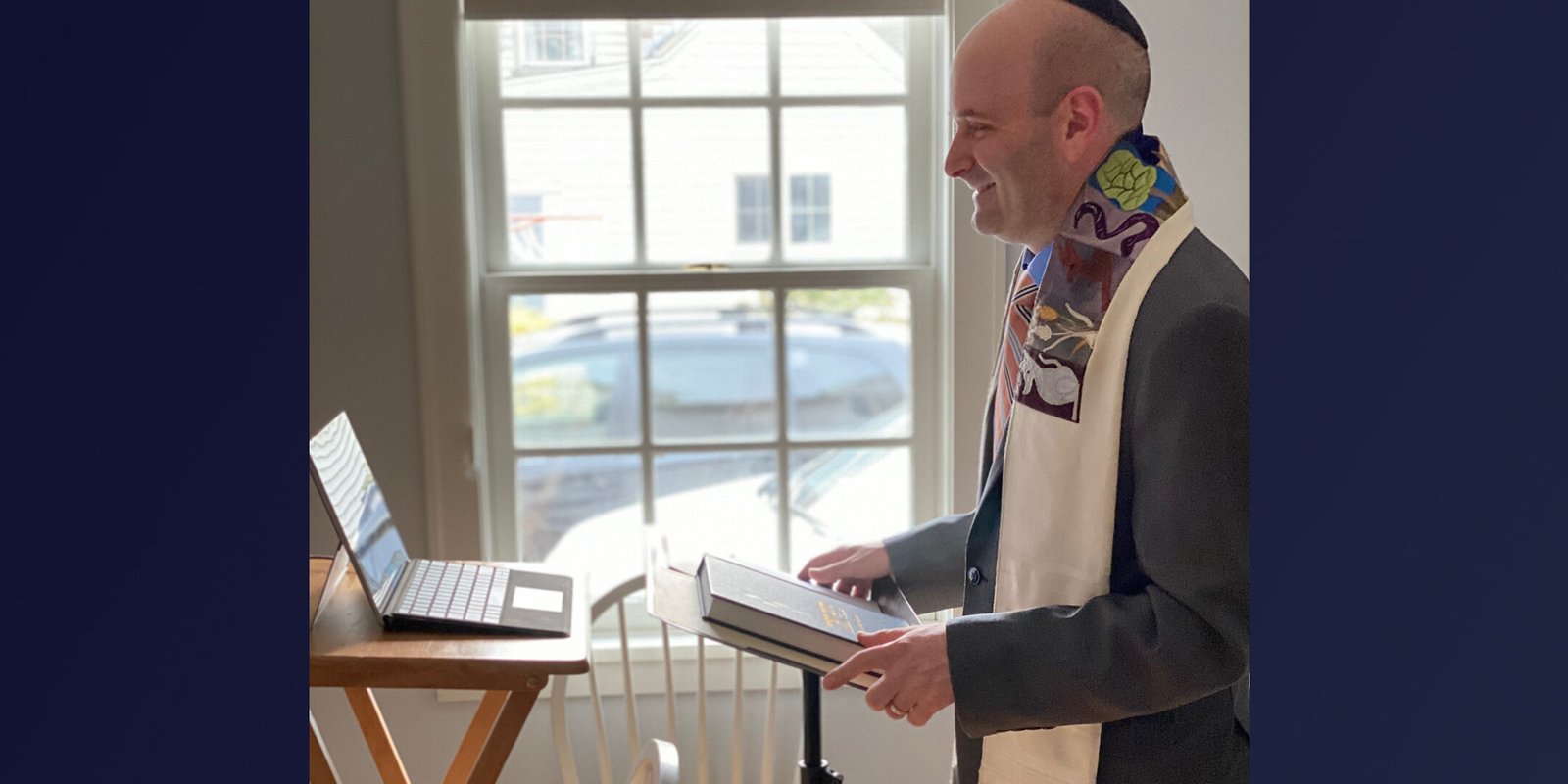

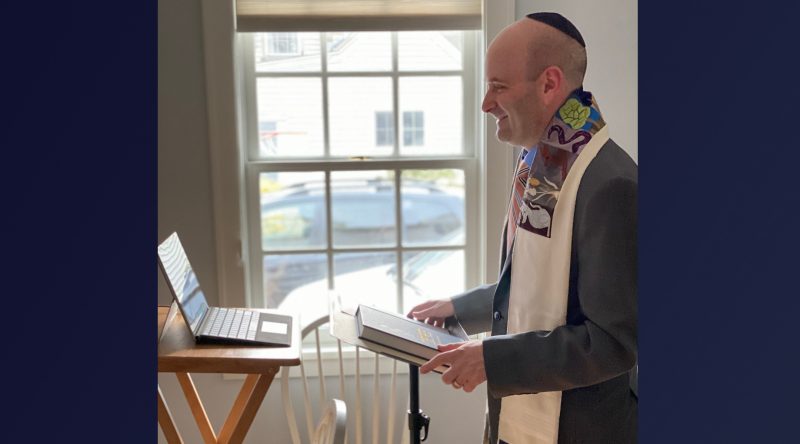

How did (and will) theology shape responses? Wertheimer notes that the more liberal branches of Judaism shifted easily to the use of technology on the Sabbath, while the Orthodox resisted, and synagogues in the Conservative movement experienced this as a fraught question, often precipitating tension between lay members who wanted streaming and rabbis who wanted to model a stricter observance of Shabbat.

Beyond Shabbat, many astute rabbis took this opportunity to expand their emphasis on observance in the home. Since people were stuck there anyway, they introduced lessons in rituals that are meant to be observed in the household. Discovering and reviving neglected practices may be a lingering boon from this time.

Liturgical practice has changed, as well. Which elements of the standard service can be cut or shortened to better fit attention spans – not just when we are watching on screen, but also when we are sitting in pews?

How were (and might) resources be deployed in new ways? Not surprisingly, Wertheimer observed that the large congregations with multiple staff members had an easier time mobilizing the technology and expertise to produce high-quality on-line experiences that were viewed by thousands from around the world. But smaller ones often took advantage of volunteers in new ways.

And as Wertheimer found, time and space were resources that could be deployed in new ways. Not only could people gather from all over the world, but they could do so on their own time and without having to commute. Taking advantage of that without losing the value of gathering will be a major challenge for the future.

For synagogues this also poses a challenge to how membership works. Will people see the value in paying membership dues when they can “get the services” for free? And on the other hand, will synagogues embrace the many Jews who participated virtually in High Holy Days observances but wouldn’t (or couldn’t) afford the traditional in-person events? Resources, culture, and theology are always intertwined.

What about the environment in which congregations exist? Will buildings return to their central role in the experience of worshiping together? How will the nature of those buildings – spacious or crowded, inspiring or boring – make a difference?

And how has the nature of the competitive environment changed? The ecology of congregations now includes all the on-line offerings people can choose from. Will they still choose to gather in a particular time and place?

Looking to the future

Wertheimer concludes that ‘what we have seen suggests that American Judaism is far more vibrant and resilient than many might have expected.’ But he also urges synagogues to ‘contemplate the unintended consequences of policies pursued during the COVID era.’ It’s an assessment every congregation needs to make, and his good questions provide an excellent guide.

***********

Jack Wertheimer is the Joseph and Martha Mendelson Professor of American Jewish History at the Jewish Theological Seminary and author of the award-winning The New American Judaism: How Jews Practice Their Religion Today, published by Princeton University Press in 2018. Professor Wertheimer was a long-time member of the Congregational Studies Team that birthed this website.